Hey, look! Reus, which entertained me splendidly and got me thinking about human nature and whatnot, isn’t the only new indie god game on the block.

Now there’s also Skyward Collapse—the latest from Arcen Games, who previously gave us A Valley Without Wind and its sequel (or was it more like a mulligan, or maybe a magnanimously meaty chunk of complimentary DLC?), as well as Tidals (a match-three puzzler that transcends the oppressive clichés of match-three puzzlers) and A.I. War (a game that, much like Dwarf Fortress, seems to be uniformly beloved among those who can figure out how the hell it works).

The folks at Arcen have a well-deserved reputation for putting big ideas and bold experiences in straightforward, plain-wrapped packages, coupling cavernously deep gameplay systems with audiovisuals that can, frankly, be a little goofy. (In Skyward Collapse, the units are static sprites that flap against one another like weightless homemade boardgame pieces, clacking and wheezing over an incongruously chill soundtrack—an aural landscape better suited to a coffee house or a ski lodge than to a game about divine intervention).

All of the interesting stuff ticks beneath these inauspicious (though functional) aesthetic trappings. Skyward Collapse completely skips the part where it trumpets its own importance or announces itself as a Very Important Game of Very Important Ideas, and skips straight to the ideas themselves.

I’ve talked a bit about how Reus flirts with a deeply cynical appraisal of human nature—with the idea that conflict and mutual destruction are all but inevitable, and that humankind’s capacity for violence can only ever be just barely kept at bay. In Reus, that idea is peripheral. It haunts the game without defining it.

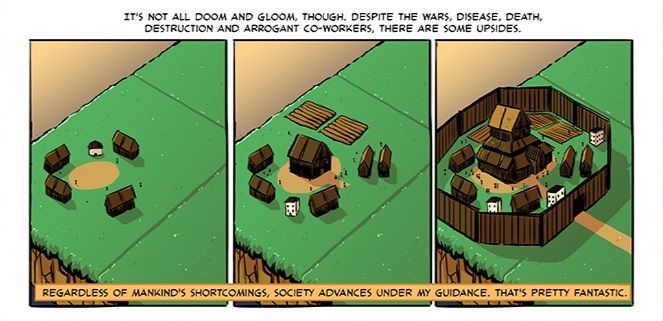

In Skyward Collapse, that cynical appraisal is the whole basis for the action. There are always two warring factions in play—no more, no less—and your goal is (immediately and fundamentally) to keep them from wiping each other out.

You can stave off apocalypse only by helping each society to keep the other in check. You exert considerable control over both sides, managing their resources and construction projects and calling down culturally specific mythical beings at will—thereby maintaining some semblance of geopolitical homeostasis as both societies grow.

The result feels a little like playing chess against yourself, except that the chess set has free will and no readily apparent interest in self preservation. Given these parameters, Machiavellian reasoning will come naturally to most players. A constant, tenuous peace is basically unachievable, and so I found myself maintaining a low, attenuated hum of perpetual warfare. Let the bandits attack that town. The Minotaur will keep them in check. (Of course, then the trick is keeping the Minotaur in check. Easier said than done).

Now, this is an Arcen game, so of course there’s more to it than that. There are “woes” to be mitigated, and uncooperative minor deities to be wrangled. But the point is always to dial up the chaos on the ground while you, from the sky, do your damnedest to maintain order, and your two ceaselessly warring factions remain the heart of the challenge.

Skyward Collapse confronts human-strife-as-a-force-of-nature much more directly than Reus does, and yet both games are fundamentally optimistic. They sanguinely encourage you to keep the humans in your charge from destroying each other for just a bit longer next time, confident that you can, even if they’ll never appreciate it, the jerks.

Maybe that’s why the music in Skyward Collapse is so chill, now that I think about it. There’s no need to panic. People are people. They are getting better, even if that progress can seem downright glacial when viewed from above.

2 Comments